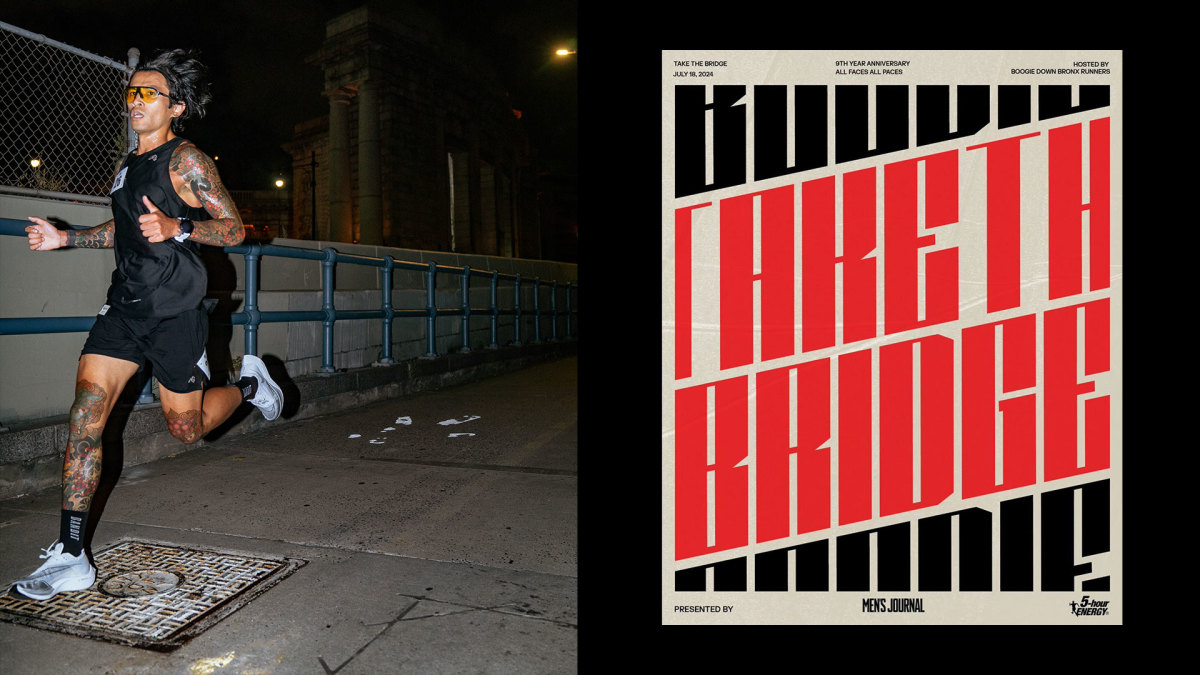

Take the Bridge is tackling the George Washington Bridge for its 9th-anniversary race.

Dave Hashim/ Ale Iaccarino

The ad didn’t offer much information. Just a black-and-white photo of a lone man running down the middle of a darkened street, a car at his heels, its headlights beaming. The link led to a registration page for something called the Midnight Half, an unsanctioned race held late on a Thursday night in May 2012. Entry was $20. I signed up immediately.

A few weeks later, I arrived at race central—a small, second-floor nightclub on the Lower East Side of Manhattan—dropped my bag upstairs, then took my place among roughly 70 runners on Chrystie Street below. Like my competitors, I had plotted my route ahead of time on MapMyRun. We were allowed to follow any course we wanted as long as we hit certain checkpoints. I determined it was impossible to complete the race in less than 13.1 miles, but I’d been running these streets for years. I hoped my familiarity would give me an edge.

To my right I recognized Lüc Carl, a bartender at St. Jerome’s, a dive bar not far from where we now stood. He looked more like a drummer of a heavy metal band. He dated Lady Gaga when she was still playing small rooms and working as a go-go dancer, and just published a book about pulling himself out of an overweight, drunken rut with pre-dawn runs. Nearly everyone else looked like the usual suspects you see in the first corral of a major road race: ropy, feather-light, focused.

View the original article to see embedded media.

As rats scurried along the empty sidewalks, the race co-director, David Trimble, announced, “The race starts when I say ‘Go.’” I knew Trimble from the Red Hook Crit, a fixed-gear bicycle race he founded in 2008 as an unsanctioned circuit on the cobblestone streets of Red Hook, Brooklyn. In 2012, he added a 5K before the main event, and the furiously fast field helped me run a 10-second PR that March.

By then, the Crit was fully permitted and illuminated by floodlights, but it still felt vaguely illicit. Meanwhile, this race that drew me to Chrystie Street well past my bedtime felt free-wheeling, if not a little dangerous.

Related: Men's Journal Partners With Alleycat Race Series Take the Bridge

Trimble said the word and we were off. Carl didn’t make it more than a block before he fell into a pothole. The rest of us charged on. As we came off the Manhattan Bridge into Brooklyn, the guys in front jumped a barricade and barreled down an unkept grassy incline to cut maybe 100 meters off the course. It was then that I realized I wasn’t in Kansas anymore. We hadn’t even gone two miles.

Some people got lost after that. A good number made it five, six, or eight miles before dropping out. Knox Robinson, founder of NYC’s Black Roses run club, took the win in 1:15, roughly five minutes slower than predicted. But with that inaugural Midnight Half, alleycat foot racing in New York was born.

View the original article to see embedded media.

More than a decade later, it’s integral to running culture. Orchard Street Runners, which co-hosted the Midnight Half, has expanded to 10 races a year, including a 30ish-mile ultramarathon around the perimeter of Manhattan called the OSR30. The Speed Project, a 340-mile relay from Santa Monica to Las Vegas, celebrated its 10th anniversary last year. And Take the Bridge, which began in New York in 2015, now stages races in cities around the world in a similar format to the Midnight Half, wherein the start and checkpoint locations are kept secret until race day.

View the original article to see embedded media.

Participants have called these races “pure,” “authentic,” “punk rock,” and “electric”—hardly the words we associate with their sanctioned counterparts. And speed alone doesn’t win the race; you have to know the streets. One friend told me recently that she loved ripping through Times Square at 1 a.m. in an OSR race, calling it “a true NYC experience.”

View the original article to see embedded media.

Admittedly, alleycat races have taken some wrong turns. In September 2021, OSR set a checkpoint inside an IKEA and placed a photographer there to capture what they presumed would be a killer photo op for the ‘gram. And yes, the stunt played well on social media; but offline, it drew a lot of fire. In my circle, we talked about how alarming it must have been for IKEA workers and shoppers when a pack of barely clothed men stormed through the showrooms at a 5-minute-mile pace. The city may be our playground, but that doesn’t entitle us to be bad citizens.

In October 2021, I launched an unsanctioned race of my own—but not an alleycat one. Having run Hood to Coast, a nearly 200-mile relay from Mt. Hood to Seaside, OR, every year since 2015, I wanted to bring the thrill of that race back to New York—albeit at a microdose. You can’t replicate running solo under a canopy of stars in rural Oregon, but you can tap into the unique joy of working as a team to accomplish something you’d never be able to do on your own.

View the original article to see embedded media.

In keeping with the theme of a track series I’d founded in 2019 called East River 5000, I decided to make it a 5x5K relay and mapped out a 15.5-mile course from the Rockaways in Queens to Brooklyn's Prospect Park. Like the races above, we didn’t close streets, obtain permits, or get funding from big apparel brands or banks. It was about as DIY as it gets.

Beach to Brooklyn was such a success that in April 2022, my partner on the East River series, Chris Forti, and I worked with Tim Rossi of the Lostboys to launch the East River Ekiden, a relay format that originated in 17th-century Japan. In our ekiden, teams of five run a total of 50K along the Brooklyn and Manhattan waterfronts, over three bridges, and through brownstone-lined neighborhoods to finish at Evil Twin Brewery in Queens, where we have a big after-party.

View the original article to see embedded media.

When people ask me why I started East River 5000, I always say I wanted to bring back the kind of events my dad raced in the ‘80s: small fields with quirky T-shirts designed by local artists that weren’t splashed with sponsors’ logos across the back. People just got together to race. It was an excuse to push themselves athletically, maybe make some new friends, and inhale pancakes afterwards. But I also hoped that if I created a race, others might follow suit, and before long the New York racing scene would be owned by the running community itself.

Ironically, the seeds for this were planted by New York Road Runners Club, as it was originally known. At the club’s founding, in 1958, NYRRC comprised a scrappy group of runners from the Bronx—most notably, Ted Corbitt, the first Black man to represent the United States in an Olympic marathon. Their vision: to make the sport accessible to everyone in the city and thereby counteract the racist and antisemitic policies of the New York Athletic Club. To that end, NYRRC charged just $1 to run the first New York City Marathon, in 1970. By 1984, the entry fee had increased to $10, and Fred Lebow, then the club’s president, told the New York Times he hoped to charge less in the future.

Today, NYRR is run more like a corporation. Its fees have ballooned in the past 20 years, and its races—almost entirely around the same predictable loop of Central Park—are all but impossible to get into without registering nearly a year in advance. To compete in just the 11 team points races—a championship series for local clubs—will cost a runner about $1,000 a year.

Unsanctioned racing allows us to break free from that monopoly and create a circuit we want, in the places people want to run, and with communities that might not be served by the major race organizers. The possibilities are limited only by our imaginations.

View the original article to see embedded media.

race embodies this spirit more than the unsanctioned 26.TRUE Marathon in Boston. Founded in 2021 and held two days before the Boston Marathon, 26.TRUE aims to celebrate Boston’s diversity by taking runners through neighborhoods its organizers feel are overlooked during Boston Marathon weekend.

Reinforcing their mission, the organizers partnered with Puma, a company that, for decades, has supported athletes who speak out for social justice—even when it was unpopular to do so.

I was one of those who dropped out of the inaugural Midnight Half. At some point around mile six, I started to question why I was hammering sub-6-minute miles on a dark street in Brooklyn. I was used to chasing lead vehicles, perfectly placed mile markers, and finish lines that made every race feel like an Olympic event. After my first Hood to Coast, I finally understood why the Midnight Half was so special.

Running isn’t only about PRs and negative splits, kudos on Strava, and mimicking the high-mileage weeks of pros. It’s also about breaking down barriers, making friends, and reclaiming agency from the corporations and brands that have tried to co-opt our sport for financial gain. With unsanctioned racing, we have the power. And if we’re lucky, we’ll experience something electric and pure—norms be damned.